Contents:-

Contents:-I. INTRODUCTION

II. LAND AND RESOURCES

A. European Plain

B. Ural Mountains

C. West Siberian Lowland

D. Central Siberian Platform

E. East Siberian Uplands

F. Southern Mountain Systems

G. Rivers, Lakes, Coastline, and Seas

H. Climate

I. Natural Resources

J. Plants and Animals

K. Conservation

L. Environment

III. POPULATION

A. Population Characteristics

B. Principal Cities

C. Religion

D. Languages

E. Education

F. Research

G. Culture

H. Cultural Institutions

IV. ECONOMY

A. Agriculture

B. Forestry

C. Fishing

D. Mining

E. Oil

F. Gas

G. Coal

H. Other Minerals

I. Manufacturing

J. Tourism

K. Energy

L. Transport

M. Currency and Banking

N. Commerce and Trade

O. Labour

V. GOVERNMENT

A. Executive and Legislature

B. Political Parties

C. Judiciary

D. Sub-Federal Administration and Local Government

E. Health and Welfare

F. Defence

G. International Organizations

VI. HISTORY

A. Origins of the Russian People

1. Invasions by Early Inhabitants

2. The House of Rurik

3. The Decline of Kiev

4. The Mongol Invasion

B. The Growing Importance of Moscow

1. The Expansion of Muscovy

2. Time of Troubles

3. Romanov Rule

C. The Russian Empire

1. Peter the Great

2. Peter’s Successors

3. Catherine the Great

4. Paul I and Alexander I

5. Nicholas I

6. Alexander II

D. The End of the Empire

1. The Revolution of 1905

2. World War I

E. Russian Revolution and the Soviet Era

F. Post-Soviet Russia

1. Yeltsin’s Presidential Rule

2. Elections and Economic Reform

3. The Putin Era

Description:-

I INTRODUCTION

|

| Climate |

|

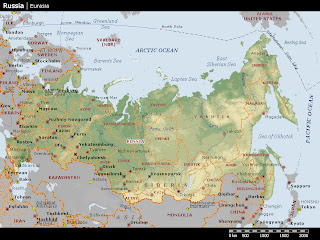

| Location Map |

The Russian Federation today comprises 89 territorial units: 21 republics, 10 autonomous okrugs (areas), 6 krays (territories), 49 oblasts (regions), 1 autonomous oblast, and two federal cities (Moscow and St Petersburg) with oblast status. In geographical extent Russia is the largest country in the world. Spanning two continents—Europe and Asia—it has a total area of 17,075,200 sq km (6,592,770 sq mi), and a total land area of 16,888,500 sq km (6,520,686 sq mi), equivalent to about one ninth of the world’s land area. North to south the country extends for more than 4,000 km (2,400 mi) from the archipelago of Franz Josef Land (in Russian, Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa) in the Arctic Ocean to the Caucasus Mountains. From west to east the maximum extent is almost 10,000 km (6,200 mi) from the Kaliningrad exclave on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea to Ratmanov (also known as Big Diomede) Island in the Bering Strait that separates eastern Siberian Russia from Alaska. Moscow (in Russian, Moskva) is the capital of Russia.

Russia’s 19,913 km (12,373 mi) of land boundaries abut on more countries than those of any other nation. On the north it is bordered by a number of arms of the Arctic Ocean comprising, west to east: the Barents, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, and Chukchi seas. On the east it is bordered by several arms of the Pacific Ocean, comprising, north to south: the Bering Strait, the Bering Sea, and the seas of Okhotsk and Japan (East Sea). In the extreme south-east, Russia borders the north-eastern tip of North Korea. On the south it is bordered, east to west, by China, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and the Black Sea. On the south-west it is bordered by Ukraine, and on the west it is bordered, south to north, by Belarus, Latvia, Estonia, the Gulf of Finland, Finland, and Norway. The Kaliningrad oblast (formerly Königsberg in East Prussia) is separated from the rest of Russia by Belarus and Lithuania. It is bordered by the latter on the north and east, by Poland on the south, and the Baltic Sea on the west.

|

| Great Kremlin Palace |

The principal island possessions of Russia lie in Arctic and Pacific waters. Farthest north, in the Arctic Ocean, is the Franz Josef Land archipelago, consisting of about 100 islands. The other main Arctic possessions, from west to east, include the two islands that constitute Novaya Zemlya, Vaygach Island, the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago, the New Siberian Islands (Novosibirskiye Ostrova), and Wrangel Island. Between these principal island possessions are numerous smaller islands and island chains. In the Pacific Ocean are the Kuril Islands, which extend in an arc south-west from the southern tip of Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula to Japan, and the large island of Sakhalin, which separates the seas of Okhotsk and Japan. The southernmost islands of the Kuril chain are claimed by Japan.

Russia is a member of the UN, having inherited the USSR’s seat, and is one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. It is also a founding member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the voluntary association of former Soviet republics that was formed on the dissolution of the USSR in December 1991; 12 of the 15 former republics are now members. In contrast to most other member states, Russia views the CIS as a vehicle for closer economic, political, and military integration, but its efforts to this end have met with little success. On May 23, 1997, Russia and Belarus signed a charter forming a union involving cooperation in a variety of spheres, including foreign policy, economic reform, energy, and transport.

II LAND AND RESOURCES

Russia can be divided into three broad geographical regions: European Russia, consisting of the territory lying west of the Ural Mountains; Siberia, stretching east from the Urals almost to the Pacific Ocean; and Far Eastern Russia (or the Russian Far East), including the extreme south-east and the Pacific coastal fringe. The majority of the country lies north of latitude 50° N, and a sizeable portion lies north of the Arctic Circle. In terms of climate and vegetation it therefore lies, broadly, within the Temperate and Polar zones. However, its sheer size means that Russia contains a wide variety of biomes, including the steppes of the south, the deserts of Central Asian Russia, the taiga of the subarctic regions, and the tundra of the polar north. The country’s agricultural resource base is limited by climate and, to a lesser degree, soils. The vastness of Russia’s territory and its varied geological formations, however, provide a rich mineral resource base that is unmatched by any other country in the world.

Both the forest-steppe and the steppe have fertile soils and together form a region, known as the black-earth belt, that is the agricultural heartland of Russia. The forest-steppe has black chernozem soils that are high in humus (organic material) content and have the right balance of nutrients for the cultivation of most crops. The forest-steppe has a better moisture supply than the steppe during the growing season, and consequently is the best agricultural area of Russia. The soils of the steppe, known as brown-steppe soils, are not quite as rich in humus as the chernozems to the north, but are very high in the minerals that are the main source of plant nutrients.

Russia’s geology is extremely complex and its varied landscapes reflect the impact of different physical processes, containing features that have evolved separately during different geological epochs. Very simply, the republic consists, in the west and north, of the world’s largest plain, fringed, on the south and east, by a discontinuous belt of mountains and plateaux. The upland and mountain regions include most of Siberia and extend to the margins of the Pacific.

A European Plain

European Russia is primarily a rolling plain with an average elevation of about 180 m (590 ft). The terrain has been formed by millions of years of water, wind, and glacial action on nearly horizontal strata (layers) of sedimentary rocks. In some places, notably the north-western border region with Finland, the softer sedimentary rocks have been eroded away, exposing the underlying basement complex of hard igneous and metamorphic rocks. The topography is generally mountainous in these areas of outcropping, particularly in the north, where a maximum elevation of 1,191 m (3,906 ft) is reached in the Khibiny Mountains of the central Kola Peninsula. Otherwise, the relief of the European Plain, with minor exceptions, is modest.

Other surface features owe their origins to glaciation during the Pleistocene ice age. Among these are several broad marshy areas, such as the Meshchera Lowland south-east of Moscow along the Oka River. This flat, poorly drained area was a lake when glacial ice blocked the streams that now partly drain it. The retreat of the glaciers, beginning about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, left behind a terminal moraine that runs east from the border with Belarus, then north of Moscow to the Arctic coast west of the Pechora River. The region to the north of this boundary is poorly drained and has numerous lakes and swamps.

B Ural Mountains

The European Plain terminates in the east at the Ural Mountains, a series of mountain ranges that were formed about 250 million years ago when, as a result of continental drift, Siberia collided with Europe during the formation of the ancient continent of Laurasia (see Plate Tectonics). Millennia of erosion have worn much of the mountains away and, today, the Urals are topographically unimpressive. The average elevation is only about 600 m (1,970 ft); Gora Narodnaya (“People’s Mountain”) in the north, is the highest point, at 1,894 m (6,214 ft) above sea level. The Urals are, however, important because they contain a wide variety of mineral deposits, including mineral fuels, iron ore, non-ferrous metals, and non-metallic minerals.

C West Siberian Lowland

To the east of the Urals the plain region continues in the West Siberian Lowland. This expansive and extremely flat area is poorly drained, and is generally marshy or swampy.

D Central Siberian Platform

Just east of the Yenisey River the rolling upland of the Central Siberian Platform begins. Elevations here average about 500 to 700 m (1,650 to 2,300 ft) above sea level. In all areas rivers have dissected, or eroded, the surface and in some places have formed deep canyons. The region’s geological structure is complex; a basement of igneous and metamorphic rocks is covered in many places by thick sedimentary rocks and volcanic lavas. The Central Siberian Platform is rich in a variety of minerals.

E East Siberian Uplands

To the east of the Lena River the topography consists of a series of mountains and basins. The higher ranges in this region, such as the Verkhoyansk, Cherskogo, and Kolyma, generally reach maximum elevations of about 2,300 to 3,200 m (7,550 to 10,500 ft). On the eastern margins with the Pacific Ocean, the mountains are higher and steeper, and volcanic activity becomes prevalent. This volcanism is caused by contemporary plate tectonic activity, that is, by the collision between the Pacific and North American plates at this point. Earthquakes are also characteristic of this area. There are 120 volcanoes on the Kamchatka Peninsula, 23 of which are currently active; the highest, Mount Klyuchevskaya, reaches an elevation of 4,750 m (15,584 ft). The volcanic mountain chain of Kamchatka continues southward in the Kuril Islands, which contain about 100 volcanoes, 35 of which are active. The formation of these islands is also the result of the collision between the two plates.

F Southern Mountain Systems

The southern border of European Russia includes the young, seismically active Caucasus Mountains, which extend between the Black and Caspian seas. The Caucasus Mountains comprise two major folded mountain chains divided along their entire extent by a lowland, with the older northern chain, the Greater Caucasus (Bolshoi Kavkaz), forming part of Russia’s southern border. Geologically complex, the mountain system is composed of limestone and crystalline rocks with some volcanic formations. The Greater Caucasus reaches a maximum elevation of 5,642 m (18,510 ft) on Mount Elbrus, an extinct volcano that is the highest peak in Europe. Other mountain ranges continue north-eastward along the southern border of central and eastern Siberia to the Pacific Ocean. Among them are the Altai, Sayan, Yablonovyy, and Stanovoy ranges.

G Rivers, Lakes, Coastline, and Seas

|

| Baikal Lake |

The longest rivers of Russia are located in Siberia and Far Eastern Russia. The largest single river system is the Ob-Irtysh; these rivers together flow some 5,410 km (3,362 mi) from western China, where the Irtysh rises, north through western Siberia to the Arctic Ocean. The second longest system is the Onon-Shilka-Amur, which flows out of northern Mongolia eastward along the Chinese-Siberian border for 4,416 km (2,744 mi) to the Pacific coast opposite Sakhalin Island. Among individual rivers, the Lena is longest; rising west of Lake Baikal in Irkutsk Oblast, it flows north through Siberia and Far Eastern Russia for about 4,300 km (2,670 mi) to the Arctic Ocean. The next longest are the Irtysh and the Ob, followed by the Volga. With a length of 3,531 km (2,194 mi), the Volga is by far the longest river in Europe. Together with its two main tributaries, the Kama and the Oka, it drains a large portion of the eastern European Plain south-east to the Caspian Sea. The fifth longest river, the Yenisey, flows north from Mongolia through eastern Siberia to the Arctic Ocean. Its main tributary, the Angara River, drains Lake Baikal. The Yenisey, which delivers 623 cu km (149 cu mi) of water to the Arctic Ocean yearly, has the largest flow of any river system in the country. It is followed by three other Asian rivers—the Lena, the Ob, and the Amur—and by one European river, the Volga. All other rivers have much smaller flows.

Historically the Volga is probably the most important Russian river. Navigable for virtually its entire length, it was the focus of early Russian trade routes, and many trading posts, fortresses, and towns developed along it during the medieval period, notably Yaroslavl, Uglich, Kostroma, and Nizhniy Novgorod. In more recent times it has been the focus of a system of waterways (rivers and canals) running from the Gulf of Finland to the Caspian Sea. Many other rivers are significant, either because they serve as transport routes or power sources in densely populated areas, or because they flow through arid regions where irrigation is essential for agriculture. Outstanding among these is the Don, which crosses the populous southern European Plain and drains south to the Black Sea and the interconnected Sea of Azov. On the northern European Plain, the Narva and Daugava (Western Dvina) rivers flow north-west to the Baltic Sea; the Pechora, Northern Dvina, Mezen, and Onega rivers flow to the Arctic Ocean and the White Sea. On the northern Caucasian Plain the two most important rivers for irrigation purposes are the Kuban, which flows west to the Sea of Azov, and the Terek, which flows east to the Caspian Sea.

The Soviet government took an active role in building large dams for power generation, irrigation, flood control, and navigation purposes, and some river basins have been almost completely transformed by the formation of series of huge reservoirs. The most extensive construction has taken place on the Volga-Kama system and on the Don on the European Plain, and on the upper portions of the Yenisey-Angara system and Ob-Irtysh system in Siberia.

Many natural lakes occur in Russia. The Caspian Sea, in the south, is the largest inland body of water in the world, with a surface area of about 371,000 sq km (143,250 sq mi). Although called a sea, it is actually a saline lake that occupies the southern end of the Caspian Depression, an area of lowland that straddles the Europe-Asia boundary in Russia and neighbouring Kazakhstan. Rivers drain into it, but water escapes only through evaporation, and over a period of time the concentration of natural salts increases. The second-largest body of water in Russia is Lake Baikal, which has a surface area of about 31,470 sq km (12,150 sq mi). Lake Baikal is the world’s deepest and oldest freshwater lake, with a maximum depth of 1,637 m (5,371 ft); it is estimated to be about 20 million years old, compared with the 20,000 years of most freshwater lakes. It also contains the greatest volume of water, about 23,000 cu km (5,520 cu mi), equivalent to about one fifth of the Earth’s unfrozen fresh surface water. The next two largest lakes, Ladoga and Onega, lie in the so-called Great Lakes Region of north-western European Russia; both have outlets to the Gulf of Finland. Like the many other freshwater lakes in this region, Ladoga and Onega owe their origin to the heavy glaciation of the area during the Pleistocene ice age.

H Climate

The harsh climate prevalent in most of Russia reflects its high latitude and the absence of moderating maritime influences. Winters are generally long and very cold; and summers are short with temperatures ranging from hot to relatively cool. The high mountains running along the country’s southern boundary largely prevent the penetration of maritime tropical air masses from the south. In the north, the Arctic Ocean is frozen right up to the coast during the long winter, preventing the ameliorating influence of relatively warm ocean waters. Because Russia lies in the northern hemisphere’s westerly wind belt, warm influences from the Pacific Ocean do not reach far inland in the east. This is particularly true in winter, when a large, cold, high-pressure cell, centred over Mongolia, spreads over much of Siberia and Far Eastern Russia.

The primary marine influence thus comes from the Atlantic Ocean in the west. However, by the time Atlantic air reaches Russia it has crossed the entire western part of Europe and undergone considerable modification. It penetrates most easily during summer, when a low-pressure system exists over much of the country; this warm, moist Atlantic air may push east well into central Siberia. Because this is the principal moisture-bearing air mass to reach Russia, most of the territory receives a fairly pronounced summer maximum of precipitation. This is fortunate for agriculture, because in most of the better farming areas the moisture supply is limited. In a number of areas, however, the distribution of summer rainfall is not advantageous—the early summer is often subject to drought, while the middle and late summer months may bring considerable rain and clouds that interfere with the harvest. This is particularly true in Far Eastern Russia, where a monsoonal inflow of Pacific air occurs during middle and late summer. In northern regions, especially from Moscow northward, featureless, overcast skies are so common, particularly during winter, that the Russians have a special name for the phenomenon: pasmurno, which may be translated as “dull, overcast, dreary weather”.

Despite the overcast skies, annual precipitation in most of the country is only light to modest. This is because much of the time the air is cool, so its capacity to hold water vapour is low. Across the European Plain, average annual precipitation decreases from more than 800 mm (31 in) in the west, to less than 400 mm (15y in) along the Caspian Sea coast. Throughout Siberia and Far Eastern Russia, annual precipitation ranges generally between 508 and 813 mm (20 and 32 in); in higher elevations annual totals may reach 1,016 mm (40 in) or more, although intermontane basins may receive less than 305 mm (12 in).

Because the climate of Russia is largely continental in type, it is characterized by temperature extremes. The coldest winter temperatures occur in eastern Siberia; air from the Atlantic Ocean tempers conditions somewhat in the west. Verkhoyansk in north-eastern Siberia is often called the “cold pole of the world”. During January, temperatures average -48.9° C (-56° F) and have reached a minimum of -67.8° C (-90° F). Absolute temperatures during winter are higher along the Arctic and, especially, the Pacific coasts; Vladivostok, for example, on the Pacific coast averages a relatively mild -14.4° C (6° F) in January; the July average is 18.3° C (65° F). However, the winds in these regions are strong, and wind-chill factors below -50° C (-58° F) have been recorded along portions of the Arctic coast. The same conditions that make for extremely cold temperatures during winter in the far north-east—isolation from the sea and narrow valleys between mountains—restrict air movement during the summer. This allows for strong heating under nearly continuous daylight at these high latitudes. During July, temperatures in Verkhoyansk average 15° C (59° F) and have reached as high as 35° C (95° F). The city has an absolute temperature range of 102.8° C (185° F), by far the greatest on Earth.

Russia encompasses a number of distinct climatic zones, which generally extend across the country in east-west belts. Along the Arctic coast a polar climate prevails, extending inland in the far east on upper mountain slopes. To the south of this zone is a broad belt of subarctic climate; in the west it reaches almost as far south as the city of St Petersburg, broadening east of the Urals to cover almost all of Siberia and Far Eastern Russia. Most of European Russia is characterized by a more humid-temperate continental climate. This belt is widest in the west; it stretches from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, then tapers eastward to include a narrow strip of the southern West Siberian Lowland. Temperate conditions are also found in the extreme south-eastern portion of Far Eastern Russia, including Vladivostok. Moscow, which lies in the temperate continental climate zone, has average temperatures of -9.4° C (15° F) in January and 18.9° C (66° F) in July. St Petersburg, which is subject to the moderating influences of the Baltic Sea, averages -8.3° C (17° F) in January and 17.8° C (64° F) in July.

A broad belt of drier steppe climate with cold winters and hot summers begins along the Black Sea coast and extends north-eastward across the lower Volga region, the southern Urals, and the southern part of western Siberia. It continues eastward in isolated mountain basins along the extreme fringes of Siberia and Far Eastern Russia, and in the northern Caucasian Plain.

I Natural Resources

Russia contains the greatest reserves of mineral resources of any country in the world. It is especially rich in mineral fuels, containing the world’s largest natural gas reserves, second-largest coal reserves, and eighth-largest oil reserves. It is also among the world leaders in deposits of iron ore, asbestos, zinc, nickel, cobalt, diamonds, potassium, lead, gold, platinum, and uranium.

Coal deposits are scattered throughout the country, but by far the largest fields lie in the Donbass (bordering Ukraine), Pechora (Arctic Circle), Kuzbass, or Kuznetsk (western Siberia), and Kansk-Achinsk (central Siberia) basins. The most developed fields are in western Siberia, the north-eastern European-Arctic region, the Moscow region, and the Urals. The country’s major oil reserves are located in western Siberia and the Volga-Ural region. Smaller deposits, however, exist in many other parts of the country, such as the Azov Sea-Black Sea area and Bashkortostan republic. The principal natural-gas deposits are in the Tyumen oblast of western Siberia, on the border with Kazakhstan; in the Orenburg oblast of south-western Russia; in the Komi republic of north-eastern European Russia; and the Yakutia (Sakha) republic in the Siberian north-east. The primary iron-ore deposits are found in the Kursk Magnetic Anomaly halfway between Moscow and Ukraine; smaller deposits are scattered throughout the country. Deposits of manganese are scattered through the Urals. Other important iron alloys, such as nickel, tungsten, and molybdenum, occur in adequate or even abundant quantities.

Russia is also well endowed with most of the non-ferrous metals, except aluminium, which is one of the country’s major mineral deficits. Aluminium ores are found primarily in the Urals, north-western European Russia, and south-eastern Siberia. Copper, on the other hand, is abundant: reserves are found in the Urals, the Noril’sk area of eastern Siberia, and the Kola Peninsula. A large deposit east of Lake Baikal became commercially exploitable when the Baikal-Amur Magistral Railway was completed in 1989.

Lead and zinc ores are abundant (often found in conjunction with copper, gold, silver, and a variety of rare metals) in the northern Caucasus, Far Eastern Russia, and the western edge of the Kuznetsk basin in Siberia. Russia has some of the world’s largest gold reserves, primarily in the Russian far east, Siberia, and the Urals. It is also a major producer of precious stones, notably diamonds. Output, mainly of industrial diamonds, accounts for about 25 per cent of the world total by value. Important deposits are located in or near the Arctic Circle. Mercury deposits have been found in the Chukchi okrug in the far north-east. Large asbestos deposits exist in the central and southern Urals and in eastern Siberia. Raw materials for the chemical-manufacturing industries are abundant in Russia. These include potassium and magnesium salt deposits in the Kama River district of the western Urals. Some of the world’s largest deposits of apatite (a mineral from which phosphate is derived) are found in the central Kola Peninsula; other types of phosphate ores are found in other parts of the country. Common rock salt is found in the south-western Urals and south-west of Lake Baikal. Surface deposits of salt are derived from salt lakes along the lower Volga Valley. Sulphur is found in the Urals. High-grade limestone, used for the production of cement, is found in many parts of the country, but particularly near Belgorod in central European Russia and in the Zhiguli Hills area of the middle Volga region.

J Plants and Animals

The broad zones of natural vegetation and soils of Russia correspond closely with the country’s climatic zones. In the far north a tundra vegetation of mosses, lichens, and low shrubs grows where the summers are too cool for trees. Permafrost, or permanently frozen subsoil, is found throughout this region. The ground is frozen to great depths and only a shallow surface layer thaws in summer allowing plants to grow.

Forests cover some 45 per cent of Russia, the greater part lying in Siberia. Taken altogether, the country’s forests account for nearly 25 per cent of the world’s forest area. The forest zone is divisible into a large northern part, the coniferous boreal forest, or taiga, and a much smaller southern area of mixed coniferous-deciduous forest.

The taiga lies south of the tundra; it occupies the northern 40 per cent of European Russia and extends to cover much of Siberia and Far Eastern Russia. Much of this region also has permafrost. Although the vast taiga zone is made up predominantly of coniferous trees, in some places small-leaved trees, such as birch, poplar, aspen, and willow, add to the diversity of the forest. In the extreme north-western part of European Russia the taiga is dominated by pines, although significant numbers of fir, birch, and other trees are also present. Eastward to the western slopes of the Urals, pines are still common, but firs predominate, and in some areas almost pure stands of birch exist. The taiga of the West Siberian Lowland is made up primarily of various species of pine, but along the southern fringes of the forest birch becomes dominant. Throughout much of the Central Siberian Platform and the mountains of the far eastern region, larch, a deciduous member of the pine family, becomes dominant.

The trees of the taiga zone are generally small and rather widely spaced. In some areas, where the local drainage is poor, there are no trees at all, and marsh grasses and bushes form the vegetative cover. The soils of the taiga are podzolic in character and infertile, having been leached of most of their plant nutrients by the abundance of acidic groundwater.

The mixed-forest zone, comprising both coniferous and broadleaf deciduous trees, occupies the central portion of the eastern European Plain from St Petersburg in the north to the border with Ukraine in the south. Coniferous evergreen trees dominate the forest in the north, while broadleaf trees are dominant in the south. The principal broadleaf species are oak, beech, maple, and hornbeam. A similar forest of somewhat different species prevails throughout much of southern Far Eastern Russia, along the middle Amur River valley and south along the Ussuri River valley. Grey-brown forest soils are found in the mixed-forest zone. They are not as infertile as those of the taiga, and with proper soil management, careful farming, and heavy fertilization they can be kept quite productive.

To the south, a narrow zone of forest-steppe separates the mixed forest from the steppes. Although now largely under cultivation, the forest-steppe has a natural vegetation of grassland with scattered groves of trees. Averaging about 150 km (95 mi) in width, this zone stretches east across the middle Volga valley and southern Ural Mountains into the southern portions of the West Siberian Lowland. Isolated areas of forest-steppe can also be found in the southern intermontane basins of eastern Siberia.

A mixture of grasses with only a few stunted trees in sheltered valleys is the natural vegetation of the Russian steppe, a large region that includes the western half of the North Caucasian Plain and a belt of land extending eastward across the southern Volga valley, the southern Urals, and parts of western Siberia. Like the forest-steppe zone, virtually all of the Russian steppe is now under cultivation.

Animal life is varied and, in places, abundant, throughout many parts of Russia. The wildlife of the tundra along the Arctic coast, northern Pacific coast, and offshore islands is surprisingly diverse, and includes the polar bear, seals, walrus, the polar fox, reindeer, pika, marmot, and the white hare. Birdlife includes white partridges, snowy owls, gulls, and loons. Geese, swans, and ducks migrate into the region during the summer, which is characterized by the appearance of millions of mosquitoes, gnats, and other insects. Fish abound in the streams. The taiga forest serves as a habitat for the European elk, brown bears, reindeer, the lynx, the sable, and a variety of forest birds, such as owls and the nightingale. Swamps in this zone have been stocked with muskrats from Canada; along with squirrels, the muskrat is now the main source of pelts legally trapped in the wild. The broadleaf forests contain wild boars, deer, wolves, foxes, minks, and a variety of birds, snakes, lizards, and tortoises. The forests of south-eastern Far Eastern Russia are the habitat of the large Siberian tiger, as well as of the Amur leopard, bears, and musk and other species of deer. The steppe is inhabited primarily by rodents such as marmots, hamsters, and five species of suslik, a type of ground squirrel. Human activities have led to the extinction, or near-extinction of most large grazing mammals, and their predators. Those that remain include the saiga antelope, although this is under renewed threat (see Conservation below), the steppe polecat, and the Tatar fox. Birdlife indigenous to the area includes the demoiselle crane, the steppe eagle, and the great and little bustard, finches, pratincoles, and kestrels and other falcons. The Caucasus region has a wide variety of wildlife, including mountain goats, the chamois, the Caucasian deer, the wild boar, the porcupine, the Anatolian leopard, the jackal, squirrels, bear, and such game fowl as the black grouse, turkey hen, and stone partridge. Reptiles and amphibians are also numerous.

K Conservation

During the Soviet era one of the world’s most important conservation and nature protection systems was established in the USSR, centred on the state nature reserves (zapovednik). These are often very large areas that are closed to all human activities except those relating to fundamental environmental research and conservation. The 89 Russian zapovednik, owned by the federal government and classified as federal natural resources, constitute approximately 40 per cent of the world’s strict scientific reserves. The country also has 29 natural monument areas and about 1,500 smaller, special-purpose reserves (zakasniki) that were established to protect endangered ecosystems, such as the steppe, or particular animal species or plants. In addition, 25 national parks and a large number of nature parks have been created over the past decade. Today, the zapovednik are still closed to the public, although under increasing pressure because of lack of funding to maintain staff and research. Lack of funds has led to the closure of a number of zakasniki, however, and many more are being opened up to tourism as a way of generating funds.

Lack of funds is not the only effect on conservation of the collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent economic and political changes. The reduction in border controls, growing poverty, increased opportunities for private enterprise, and the growth of organized crime have created major problems. The opening up of the economy to foreign investment, for example, has increased significantly the destruction of the Siberian forest. Western and Asian logging firms are now working in the area, and it is estimated that some 38,850 sq km (15,000 sq mi) of forest are now being cut every year. For conservationists the problem is made worse by the fact that up to 40 per cent of the trees cut down are left to rot in situ because of poor infrastructure and transport problems. Deforestation has been particularly bad in the Irkutsk oblast and the Khabarovsk kray, and parts of Sakha (Yakutia) republic in recent years.

Russian wildlife has been especially badly hit by recent economic and political changes. According to both local conservation experts and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), there has been an explosion in poaching, including into previously closed areas, and in smuggling. Russia is today one of the world’s major centres of the illegal wildlife trade, supplying particularly the Chinese traditional medicines market. The Siberian tiger, the world’s largest tiger, is hunted both for its pelt and “medicinal” parts, and is now on the verge of extinction in the wild, with only about 150 animals thought to be left; the species is, however, considered safe from total extinction thanks to the world’s largest and longest captive breeding programme.

Other animals severely affected by the wildlife trade include the musk deer, the Saiga antelope, the Amur and Anatolian leopards, the polar bear, brown and black bears, the Horsefield’s tortoise, the wild sable, the ibex, the walrus, and falcons and owls. It is estimated, for example, that more than half of Russia’s musk deer, which live in far south-eastern Russia and which are hunted for their glands, have been killed since the early 1990s. The Saiga antelope nearly became extinct at the end of the 19th century, but protection enabled its numbers to recover to more than 1 million by the end of the 1980s. It is under renewed threat today from hunters seeking its horn for the medicinal market; they are attracted by the high prices, which are well above most state wage levels. The leopards, like the Siberian tiger, are hunted for their bones and skins, while the bears are hunted for their pelts and gall bladders, which play an important role in Chinese traditional medicine.

It is not only the wildlife trade that is affecting Russian wildlife. The Baikal seal, known also as the nerpa, is the world’s only freshwater seal. It is being threatened by illegal hunting to supply mink and sable farms with meat, by pollution, and by excessive culling to protect fish stocks. Overfishing, the vast majority of it illegal, is the main problem facing the sturgeon, whose eggs are eaten as caviare. The WWF has estimated that the world’s sturgeon population has declined by up to 70 per cent in recent years; most of the damage is being done in the Caspian Sea, the source of 90 per cent of the world’s caviare.

L Environment

Although Russia contains huge tracts of unspoilt forest and tundra, the preoccupation with heavy industrialization, agricultural expansion, and the defence industries during the Soviet era has left it with huge environmental problems. These range from unsafe nuclear power plants and decommissioned nuclear submarines, to air, water, and soil pollution, and soil degradation. Almost 15 per cent of Russian territory is thought to be severely environmentally damaged, with much larger areas also facing serious problems.

The worst-affected areas include the major industrial cities, parts of western Siberia and the Arctic, as well as the Nikel area of the Kola Peninsula in north-eastern Russia, near the border with Norway. Environmental monitoring in Norway has shown that some 750 sq km (290 sq mi) around the Nikel nickel smelter has suffered “total environmental deterioration”; in another 2,000 sq km (772 sq mi) there has been extensive damage to vegetation. In western Siberia and inside the Arctic Circle, probably the major causes of environmental degradation are the oil industry and mining. Waste products from both industries are discharged into rivers. In addition, large areas have been affected by oil spills and by leaks from the country’s ageing oil pipeline network. Up to 10 per cent of production is believed to be lost in transit each year, while individual large spills have topped 500,000 tonnes.

One aspect of the 1986 disaster at Chernobyl (now in Ukraine) has been to focus attention on the safety and environmental aspects of the nuclear power facilities of the former USSR. Russia has the lion’s share: more than 50 industrial and research reactors. All are suffering from the effects of age and inadequate maintenance, and many also suffer from labour problems. Additionally, 16 are of the unsafe RBMK (Chernobyl) type. Between 1992 and 1994 more than 260 accidents were reported in these 50-plus reactors, some of them potentially as serious as the Chernobyl breach. Russia also faces a legacy of nuclear-related problems from its defence industry, including: what to do with more than 100 nuclear reactors from decommissioned submarines, the environmental impacts of past nuclear testing, and the dumping of nuclear waste in the northern Barents Sea and in the Kara Sea. The latter is the most radioactive sea on the planet, according to Russian environmentalists, and is located next to Russia’s main underground nuclear testing ground, the island of Novaya Zemlya. Underground nuclear testing also took place in the Sakha republic in north-eastern Siberia during the 1970s and 1980s; dead forests now surround the test sites and the permafrost is radioactive.

More than 80 million Russians live in areas where concentrations of air pollutants are well in excess of permissible levels as a result of industrial emissions and, increasingly, pollution from motor vehicles. It is estimated that 30 to 40 per cent of all children’s diseases are the result of air pollution, while general respiratory diseases like bronchial asthma have increased sixfold since the early 1990s. Another problem affecting human health relates to water supplies. A large percentage of rivers generally, and drinking water supplies in particular, are polluted by industrial effluents, by the run-off of fertilizers and pesticides from agricultural land, and by sewage, only a small percentage of which is properly treated before discharge. The pollution of many rivers, including the Don, Moskva, Northern Dvina, Tobol, Ufa, and Ural, is at critical levels. Some rivers, such as the Tom’, Obi, and Yenisey, have been characterized by environmentalists as “open sewers”. The health impact of water pollution ranges from reduced life expectancies and increased levels of still births and congenital deformities in the worst-affected areas, to a doubling of cases of intestinal infections, including dysentery, typhoid, and viral hepatitis.

Such pollution has had a significant role in the environmental problems facing the Black and Caspian seas, albeit not all of Russia’s making in both cases. Marine life in the Black Sea is close to extinction because of the impact of the heavily polluted rivers that feed it. In addition to raw sewage, nitrates and phosphates from agriculture, detergent residues, and heavy metals, the Black Sea has also been affected by radioactive contamination from Chernobyl. The Caspian Sea receives about 25 per cent of Russia’s annual sewage production. It is also contaminated by the dumping of solid waste, and by spills and other pollution from the offshore oil industry. Pollution is not yet as bad as in the Black Sea, however, and efforts are being made to develop coordinated environmental policies.

Since about 1992, the government has begun establishing environmental policies. An environment ministry has been set up and progressive legislation has been passed, introducing a pollution-fee system. Taxes are levied on air and water emissions, and on solid waste disposal, with the resulting revenues channelled to environmental protection. This legislation has yet to have a significant impact, however, in part due to the many other problems facing the country. In the early 1990s less than 5 per cent of the money raised from pollution taxes was used for environmental protection. Many of the worst polluters are the heavy industrial concerns set up during the Soviet era in remote areas, like Nikel, where problems associated with minimal pollution controls have been compounded by lack of maintenance. The government does not have the necessary funding to modernize them, but with no alternative sources of employment in many of these areas it has also generally been reluctant to close them down.

Environmental concerns within the population are also growing; a Green Party and various lobbying organizations have been established. Environmental protest has a long history in some areas, notably Lake Baikal. Concern about the impact of industrial development began in the 1960s with the construction of the huge Baikalsk pulp and paper mill on the southern shore. Lobbying led to the imposition of strict emission controls on the plant, which environmentalists have continued to monitor. In 1992 Lake Baikal was made into a national park; in 1996 it became a World Heritage site. The lake is one of three natural World Heritage sites recently established in Russia—the others being the Virgin Komi Forest in the Ural Mountains (listed 1995) and the Kamchatka Peninsula (1996)—and the government is seeking to have more sites included on the list as part of environmental protection efforts.

III POPULATION

With a total population of about 145,470,200 (2001), Russia is one of the world’s most populous countries. More than 100 nationalities inhabit Russia, making it one of the largest multinational states in the world. Russians, a Slavic people, are the predominant nationality, comprising more than 80 per cent of the total population. The largest of the non-Russian minorities, the Tatars, comprise only 3.8 per cent of the total. The Ukrainians (3 per cent) and the Chuvash (1.2 per cent) are the only other minorities constituting more than 1 per cent of the population. Other minorities include Avars, Armenians, Bashkirs, Belorussians, Jews, Germans, Mari, Moldovans, and Udmurts.

A Population Characteristics

The overall population density of Russia is about 9 people per sq km (22 people per sq mi). Population distribution across the country, however, is extremely uneven. The population density of a particular area generally reflects the land’s agricultural potential, with localized population nodes occurring at mining and industrial centres. Most of the country’s people are concentrated in the so-called fertile triangle, which has its base along the western border between the Baltic and Black seas, and then tapers eastward across the southern Urals into south-western Siberia. Although the majority of the population remains concentrated in European Russia, there was substantial eastward migration after World War II, especially to southern Siberia and Far Eastern Russia as new industries and farming areas were opened up.

Throughout much of rural European Russia the population density averages about 25 people per sq km (65 per sq mi). The country’s heaviest population densities are found in sprawling urbanized areas, such as the Moscow oblast. More than one third of Russia has a population density of less than 1 person per sq km (2.6 per sq mi). This includes part of northern European Russia and huge areas in Siberia.

The demographic structure of Russia has undergone profound changes over the past decade or so, with the greatest changes during the 1990s. Like other economically more developed countries, Russia’s birth and fertility rates have been declining over many decades. Official figures, however, show that this trend has intensified since the mid-1980s. The birth rate has halved, from nearly 20 live births per 1,000 population in the mid-1980s to 9.35 per 1,000 in 2001. During the same period the total fertility rate—the average number of children born to a woman during her reproductive life—has registered one of the largest falls among the economically more developed countries. Russia’s total fertility rate during the second half of the 1980s averaged 2.1 children born per woman, the rate usually considered to be the minimum necessary to maintain existing population levels. By 2001 it had fallen to just 1.3 children born per woman, one of the lowest rates in the world.

Mortality rates, by contrast, have shown a dramatic reversal of the downward trend that has characterized the modern era. The overall death rate has jumped from about 10.5 per 1,000 in the mid-1980s to 13.8 per 1,000 in 2001. Infant mortality rates have also risen, from 19.9 deaths per 1,000 live births in the late 1980s to 20 per 1,000 in 2001. The rise in mortality is reflected in the sharp decline in life expectancy during the 1990s, from an average of almost 69 years for the population as a whole at the early 1990s to 67 years in 2001. This is one of the worst figures among economically more developed countries, comparing for example with an average life expectancy of about 77 years in the countries of the EU. The average figure also conceals sharp differences between the sexes. Male life expectancy has fallen since the start of the 1990s, from an average of 64 years to just 62 years in 2001. The decline in female life expectancy, however, has been less, from 73 years to 73 years.

The impact of these demographic changes means that in Russia deaths outnumber births. In 1989 there were 1.6 million deaths and 2.2 million births; by 1995 the figures had reversed, with 2.2 million deaths and 1.4 million births. The result is a rapidly declining population that is beginning to cause concern to the authorities, who fear depopulation of many of the more remote areas. Russia’s population growth rate is now -0.35 per cent (2001). Overall, the country’s population has fallen by more than 600,000 since 1992; if the effects of migration are excluded the decline is nearer 2 million.

The change in Russia’s population structure reflects a variety of factors. The large drop in male life expectancy, for example has been attributed to the high levels of alcohol consumption and smoking among Russian men, as well as to the psychological stresses created by the rapid changes in the economy, rising unemployment, and increased uncertainty. Russian researchers have identified the greatest rise in mortality among poorly educated, unemployed urban males, who have been unable to adapt to the country’s new economic conditions. A general deterioration in health levels due to a worsening of people’s diet as a result of rising food prices, and to poor environmental conditions, especially air and water pollution, have contributed to the general rise in mortality levels. So too have the shortages of medicines and vaccines, and the deterioration in state-run medical services generally, that have resulted from funding cuts. There has been a marked increase in levels of preventable diseases such as diphtheria and tuberculosis, as well as in bronchial asthma and other respiratory diseases, dysentery, and typhoid.

B Principal Cities

Almost 77 per cent of the population lives in urban areas. Russia became a country of large cities despite government restrictions during the Soviet period designed to limit the populations of major urban centres. Thirteen cities have more than 1 million inhabitants; most of these are in European Russia. Another 80 have populations of between 1 million and 200,000. The largest city by far is Moscow, the capital, with a population of 8,297,900 (1999 estimate). St Petersburg (called Leningrad during the Soviet era), which served as the national capital from 1712 to 1918, is the country’s second city. It is situated on the Gulf of Finland, a leading port and a primary industrial centre, and has a population of 4,695,400 (1999 estimate). The third-largest city, Nizhniy Novgorod, the largest city on the Volga and a major automotive and shipbuilding centre, has a population of 1,361,500 (1999 estimate). Novosibirsk, the largest city in Siberia, has a population of 1,402,100 (1999 estimate). Yekaterinburg (Sverdlovsk), the largest city in the Urals, has a population of 1,270,700 (1999 estimate). Samara (Kuibyshev), a commercial centre of the middle Volga region and the primary refining centre for the Volga-Urals oilfields, has 1,170,800 inhabitants (1999 estimate). Omsk, the second-largest city in western Siberia and the region’s chief petrochemical centre, has 1,157,600 people (1999 estimate).

The other cities with more than 1 million inhabitants include Chelyabinsk, the second-largest urban centre in the Ural Mountains; Kazan, capital of the Tatar republic, located on the middle Volga; Perm’, the major industrial centre in the Kama River region to the west of the Urals; Ufa, an important petrochemicals centre in the southern Urals; Rostov, a commercial, industrial, and transport centre in southern European Russia on the lower Don River; and Volgograd, a centre of machinery production and other industrial activity, on the lower Volga.

C Religion

Religious expression, which was controlled by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and strictly discouraged for nearly seven decades, has unfolded in a myriad of different beliefs, sects, and religious denominations since the dissolution of the USSR. Missionaries from abroad and other proselytizers have introduced a wide variety of religious beliefs and new-age philosophies to Russia. The religious revival, however, has resulted primarily in the resurgence of traditional religions, particularly Orthodox Christianity, but also other forms of Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism.

Russian Orthodox Christianity (see Orthodox Church), adopted by the Eastern Slavs from the neighbouring Byzantine Empire in the 10th century, is the primary religion in Russia, with an estimated 35 million to 40 million adherents (about one quarter of the population). The head of the Russian Orthodox Church is the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia (from 1990 Alexii II of St Petersburg and Novgorod), assisted by the seven-member Holy Synod. The Church is widely respected by Russian non-believers, who see it as a symbol of Russian heritage and culture. Orthodox holidays are officially observed by the Russian government, and politicians attend major Church festivals. The Church is divided, however, on its role in a post-Soviet society. An anti-Semitic, highly nationalistic, intolerant faction is opposed by another group advocating a more tolerant, ecumenical approach to worldly affairs. Another challenge to its authority outside Russia has been the resurrection of the Uniate Church in Ukraine, which observes Orthodox rites but recognizes the supremacy of the Roman Catholic pope.

Other traditional Christian denominations include the Old Believers, whose schism from the Orthodox Church dates from the 17th century; the Armenian Apostolic Church; and the Roman Catholic Church. In the mid-1990s there were estimated to be 300,000 Roman Catholics in European Russia and 122,000 in Siberia.

Most Muslims in Russia practise the Sunni form of Islam. Islam is the dominant religion among peoples of the north Caucasus, such as the Chechen and the Ingush, and in the middle Volga region, among the Tatars, Chuvash, and Bashkirs. Buddhism has been an official religion in Russia since the mid-18th century, and is most widespread in the Buryatia republic, where the Central Spiritual Department of Buddhists of Russia has its seat, in the Kalmykia and Tuva republics, and in parts of the Irkutsk and Chita oblasts. There are also newly established communities in Moscow and St Petersburg. Although many Jews have left Russia (and previously the USSR) since the relaxation of emigration rules during the 1970s, the country still has a sizeable Jewish population—around 656,000 in the mid-1990s—living mainly in urban areas, but also in small communities around the country including Yevreyskaya (Birobidzhan), the Jewish autonomous oblast in the far east.

Since the passing of the 1990 law allowing religious freedom, there has been a rapid rise in the number of other religious groups. Although the most dramatic growth has been among evangelical Christian sects, including Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Seventh-Day Adventists, other groups have also established themselves—including Japan’s Aum Shinri Kyo fringe cult, which was implicated in the 1995 Tokyo subway gas attack. The rise in non-traditional religions generally, and particularly the presence of large numbers of well-financed foreign missionaries, has created considerable unease and resentment within conservative religious and nationalist circles in Russia. In July 1996 Aleksandr Lebed, then the Russian security chief, reflected the feelings of many ordinary Russians when he called for the banning of all foreign religions. Yeltsin rejected such action, but many local administrations, particularly in strongly Muslim and Buddhist areas, are reported to have taken independent action, issuing restrictive decrees and laws.

D Languages

More than 100 languages are spoken in Russia, and some of the republics have declared their own local state languages. The Russian language, however, is the most commonly spoken in business, government, and education. Russian was established as the dominant language during the Soviet period, reflecting the dominance of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic within the former USSR and the dominance of Russians within the state government and bureaucratic structures. As a result, Russians speak their native tongue almost exclusively—in 1989 only 4.1 per cent of Russians throughout the former USSR could speak another indigenous language—while most other ethnic groups are bilingual. Millions of non-Russians have adopted Russian as their mother tongue. The government of the former USSR helped many smaller ethnic groups to develop their own written alphabets and grammars; however, through educational policies, it also ensured the dominance of the Russian language.

E Education

Russian education and cultural institutions and activities, highly constrained and monitored, as well as financed, by the Soviet state for nearly seven decades, were granted much greater freedom during the late 1980s, under the policy of glasnost (Russian, “openness”) of the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Liberalization accelerated with the collapse of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the USSR. Ideological training has disappeared; new teaching methodologies have been developed and promoted in public schools, including a new approach to Soviet and Russian history; private schools have been established; and the bans on a variety of forms of artistic expression have been lifted. However, although now free of ideological and political interference, Russia’s educational system and cultural institutions have been severely affected by the impact of the liberalization of the country’s economy generally, and by the collapse of government finances in particular. State funding has been cut or, in many cases, ended and even where theoretically still provided has often failed to materialize.

Russia inherited a well-developed, comprehensive system of education that was probably one of the greatest achievements of the Soviet period. The Soviet authorities established an extensive network of pre-school, elementary, secondary, and higher-education institutions that transformed national educational levels. Literacy levels were brought up to almost 100 per cent, compared with a predominantly illiterate population in 1917, secondary-level education became the norm, with a sizeable minority going on to higher education, and the country became a world leader in many areas of research. It also provided free continuing education for adults. At the age of six or seven, children in the USSR entered primary school for an intensive course from grades one to four. Intermediate education began with grade five and continued until grade nine. After that, children entered upper-level schools, specialized institutions, or vocational-technical programmes, which included on-the-job training.

Nurseries, kindergartens, and other early-education facilities were particularly well developed in Russia during the Soviet period. In 1989 nearly 70 per cent of pre-school-age children attended a state-run facility—one of the highest proportions among the former Soviet republics. The system of specialized secondary and vocational-technical education was also well developed. In 1989 Russia had 2,595 specialist secondary institutions, or 57 per cent of the total in the former Soviet republics. Such schools were set up to train skilled and semi-professional workers such as technicians, nurses, and elementary-school teachers, who generally function as assistants to professional graduates of higher educational institutions. Vocational-technical schools offer students a chance to complete a general secondary education while obtaining occupational training.

Russia has some 70,000 primary and secondary schools, including some 447 non-state schools (1994). More than 21 million pupils were enrolled in 1994, equivalent to about 95 per cent of the total school-age population; 40,000 of the total were in private schools. Although primary and secondary education are still free in the state sector, schools are facing increasing shortages of equipment and books, and school buildings are generally in a poor state of repair; many schools lack basic facilities such as running water or sewerage. There is also a growing problem of staff shortages. Teachers’ salaries are very low (equivalent to about 73 per cent of the average national wage in 1994) and the status of the profession, which is dominated by women, has fallen considerably in recent years. Many teachers, particularly those with marketable skills like foreign languages, have left to take up jobs in the expanding and more lucrative private sector, while the number of entrants to the profession is falling. The problem of low wages has been compounded by the government’s financial problems, which have led to a large backlog of unpaid wages in the public sector generally. Schoolteachers have been in the forefront of strikes to protest against the backlog.

The impact of economic liberalization and government financial shortages on the pre-school sector has been even more profound. The state nursery sector, set up originally to support the Soviet Union’s large number of working women, by caring for children aged 6 months to 3 years, had virtually ceased to exist by the end of 1995. To help compensate for this loss, the government in 1994 increased maternity-leave provision from 1 to 3 years, and many women have taken advantage of this, although the additional leave is unpaid. Private crèches have been set up, but the cost of their fees mean that they are out of the reach of most parents. Kindergarten provision for children aged 3 to 6 years has continued. However, many of the free workplace facilities of the Soviet era have been closed down by privatized state industries, while nurseries still in the state sector have lost their subsidies, forcing them to charge fees.

The number of higher educational institutions has expanded since the collapse of the USSR, rising from 514 in 1990 to 553 in 1994. The increase reflects mainly the rapid growth of non-state higher educational institutions during the 1990s. In 1994 there were 157, equivalent to 28 per cent of total higher educational institutions. However, the number of students enrolled in higher education has fallen, from 2.8 million in 1990, to just over 2.5 million in 1994, of whom 4 per cent were in the non-state sector. The fall in numbers has been due partly to Russia’s changing demographic structure, but mainly to the introduction of tuition charges for students. Although the fees are generally low, except in the most prestigious universities, by the end of 1996 the only university still providing completely free access was Kazan State University in Tatarstan republic. Founded in 1804, Kazan State University is the third oldest university in Russia, and also one of the most prestigious. The others included Moscow State University (founded 1755), St Petersburg State University (1819), and Novosibirsk State University (1959). Other important universities are located in Rostov, Nizhniy Novgorod, Tomsk, Vladivostok, and Voronezh. The number of universities has increased since 1991, created from numerous small institutes in cities of republics across the federation. Notwithstanding this, universities still comprise only a small proportion of higher educational establishments; the vast majority are institutes that specialize in vocational training.

Undergraduate training in higher educational institutions generally involves a four- or five-year course of study for full-time students. However, a large minority take their degree by correspondence course or attend on a part-time basis. Students completing undergraduate courses can enrol for graduate training for a one- to three-year term. Graduate students who successfully complete their courses of study, comprehensive examinations, and the defence of their dissertations receive candidate of sciences degrees, which are roughly equivalent to doctoral degrees in the West. A higher degree, the doctor of sciences, is awarded to established scholars who have made outstanding contributions to their disciplines.

F Research

During the Soviet era the state channelled large amounts of funding into research and the USSR achieved a prestigious reputation in a wide variety of fields, including nuclear physics, space science and technology (including astronomy), medicine, Earth sciences, and the biological sciences. Research was, and still is, carried out not only in universities but also in a large number of independent research institutes; in 1996, Russia had more than 1,000 such institutes of various kinds, for pure and applied research. Those relating to pure research are mainly organized within coordinating academies. The most important of these is the Russian Academy of Sciences (formerly the Academy of Sciences of the USSR), which is the chief coordinating body for research in the natural and social sciences in Russia, controlling a network of around 300 research establishments. There are also specialized academies for the agricultural sciences, the arts, the medical sciences and education.

G Culture

Russia has an enormous cultural legacy, notably from the 19th century; its achievements in music, ballet, drama, literature, and film are particularly renowned. Russia has produced some of the most famous names in 19th and 20th century music, notably the composers Alexander Borodin, Mikhail Glinka, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Rachmaninov, Nicolay Rimsky-Korsakov, Aleksandr Scriabin, Igor Stravinsky, and Peter Illich Tchaikovsky. Other famous names are the singer Chaliapin and the musicians Vladimir Horowitz, Anton Rubinstein, and Emil Gilels. Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky are among the Russian composers who have had a close association with the ballet. Of all the performance arts, ballet is arguably the one most closely associated with Russia. It was the main home of classical ballet as it developed during the second half of the 19th century, largely under the direction of French-born choreographer Marius Petipa. In the 20th century the company of Sergei Diaghilev, Ballets Russes, with legendary names like dancer Anna Pavlova and the dancer-choreographers Vaslav Nijinsky and Michel Fokine, provided the impetus that revitalized ballet all over the world. In the modern era, the Bolshoi Ballet and the Kirov Ballet continue the classical tradition. Famous names include Galina Ulanova, Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and Irek Mukhamedov.

The 19th century was also probably the richest period for Russian writers, beginning with poet and author Aleksandr Pushkin, and including Mikhail Lermontov, Nikolay Gogol, Ivan Turgenyev, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Anton Chekhov. Famous names of the 20th century include Maksim Gorky, Boris Pasternak, Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Sholokhov, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Joseph Brodsky. In the visual arts the most famous names include Andrei Rublev and Theophanes the Greek, artists whose work in the late 14th and early 15th centuries marked the supreme achievement in icon painting. More recent names include the artists Wassily Kandinsky, Ilya Repin, Léon Bakst, Kasimir Malevich, Alexander Rodchenko, and Vladimir Tatlin. Russia’s noted film-makers include Andrey Tarkovsky, Mark Donskoy, and Sergey Eisenstein.

For more details of Russian culture see Russian Cinema; Russian Literature.

H Cultural Institutions

Russia has a huge number of museums of all kinds, including outdoor museums of architectural preservation. Most of the major ones are in Moscow and St Petersburg. Best known to tourists are the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, one of the world’s finest museums, and the Armoury Museum in the Moscow Kremlin. Also in Moscow are the State Tretyakov Gallery, with a collection devoted to Russian art, the Pushkin Museum of Fine Art, the Folk-Art Museum, the Central Museum, and the Museum of the Revolution, as well as many other smaller, more specialized collections. The Permanent Exhibition of National Economic Achievements in Moscow offers a large display of achievements in science, industry, and agriculture. To the north-east of Moscow there is a string of a half-dozen old kremlin (citadel) towns that served as seats of government for city-states during the Middle Ages. These have been restored as part of a tourist circuit known as the Golden Ring.

Russia also has thousands of libraries of various kinds. Best known is the Russian State Library in Moscow, which is one of the largest library collections in the world. Other leading libraries include the State M. E. Saltykov-Shchedrin Public Library in St Petersburg, the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Moscow State University Library.

The best-known theatres in Moscow are the Bolshoi (“big”) Theatre, the Maly (“small”) Theatre, and the Moscow Art Theatre. In addition, many of the larger productions of the Bolshoi ballet and opera companies are presented in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses, which seats 6,000 people. Other theatres of note in the capital are the Moscow Central Children’s Theatre, the Moscow Young Spectators Theatre, the Moscow Central State Puppet Theatre, the Moscow Art Theatre, the Academic Musical Theatre, the Operetta Theatre, and the Theatre Art Institute. St Petersburg has the Mariinsky Theatre, the Maly Opera Theatre, and the Pushkin Academic Drama Theatre.

Russia’s cultural institutions have been greatly affected by the heavy cuts in public spending and the country’s other economic problems. The generous subsidies given to the arts during the Soviet era have left the country with an enviable cultural infrastructure, but one that is also extremely expensive to maintain. Russia’s theatres, orchestras, opera companies, circuses, libraries, museums, and other cultural institutions were all totally dependent on state funding. State patronage also supported writers, artists, and film-makers. A number of cultural institutions have been forced to close down, while many others are on the brink of closure. Some are attempting to compensate for funding cuts by raising finance commercially, such as through corporate sponsorship and donation, although this is a route open so far only to the most famous. Foreign tours have been a vital source of finance for some institutions, such as the Kirov and Bolshoi ballet companies. There have also been attempts to pressure the government and local authorities to release funds that have been allocated but not disbursed, a common occurrence. In October 1996, for example, the country’s museum directors mounted public protests in an attempt to persuade the Ministry of Culture to release funding allocated for maintenance.

IV ECONOMY

As in other former Soviet republics, Russia has experienced formidable economic difficulties since the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. Efforts to move from the old centrally planned economy to a market-oriented one have met with varying degrees of success. The break-up of the USSR into 15 independent states destroyed important economic links that have been only partially replaced. As a result of this dislocation and of the government’s failure to implement a consistent reform programme output dropped by more than one third between 1990 and 1996. Real gross domestic product (GDP) declined by some 40 per cent during the same period, a much greater drop than occurred in the United States during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Real investment has declined by similar percentages, while during the first half of the 1990s both inflation and unemployment rose sharply. The value of Russia’s currency, the rouble, dropped rapidly, from the highly artificial official rate of 0.6 rouble per US$1 in 1988 to more than 1,000 roubles per US$1 in 1993. Official unemployment was about 8 per cent, but real levels of unemployment and underemployment were much higher than this. In addition, the government had inherited both a large government deficit and a large foreign debt from the Soviet period; the deficit in 1993 equalled about one fifth of total GDP, while Russia’s foreign debt was in the region of US$80,000 million.

In January 1992 the government launched an economic reform programme aimed at giving new life to a process that had stagnated since the initial introduction of economic reforms by Mikhail Gorbachev in the mid-1980s. The measures were met with widespread resistance by industrial managers and conservative members of the State Duma. Largely in response to this resistance (and to the annoyance of the government) the Central Bank of Russia extended large subsidies to inefficient enterprises in 1992. In mid-1993, however, the bank began to adhere to governmental directives on subsidies, and other elements of the reform programme began to be implemented. By the end of 1995 nearly all prices had been freed, defence spending slashed, the old centralized distribution system ended, private financial institutions established, foreign trade decentralized, and the world’s largest privatization programme was well under way. By 1995 the non-state sector was producing about 70 per cent of GDP, compared with about 60 per cent in 1993. On the other hand little or mixed progress had been made in other areas that were key to providing a solid foundation for the transition to the market economy. For example, the legislation permitting the private ownership, selling, and renting of land was not passed until October 1993, when President Yeltsin issued a decree that repealed a ten-year moratorium on reselling land that had been imposed by the legislature. The State Duma continued, however, to prevaricate on the introduction of legislation that would allow the development of a land market as a source of capital, and the fledgling securities market remained largely unregulated.

During 1995 and 1996 there were some indications that the economy was starting to move out of extreme recession. Inflation had been cut to less than 32 per cent by September 1996, from 130 per cent in 1995 and 849 per cent in 1993, while the decline in output, real GDP, and gross capital investment had slowed considerably. In 1995 and 1996 real GDP fell by 4 per cent and 2 per cent respectively, compared with 12.6 per cent in 1994; industrial output declined by 3 per cent and 4 per cent respectively, compared with almost 21 per cent in 1994; and gross capital investment fell by 13 per cent and 7 per cent respectively, compared with 24 per cent in 1994. By late 1996 most analysts were projecting modest growth in all these indicators in 1997. However, official figures published in June 1997 indicated that the long-awaited upturn in Russia’s economy was still some time away. The government was projecting that GDP, industrial output, and investment would continue to fall, by between 2 and 4 per cent, during 1997.

The causes of the Russian economic crisis have been, as already indicated, the disruption of traditional trade patterns and a delay in enacting economic reforms. Trade between Russia, other former Soviet republics, and Eastern European countries has declined markedly since the late 1980s, when Eastern European countries achieved independence from Moscow, and the Soviet-controlled, centralized system of trade and production began to disintegrate. Trade between Russia and other republics of the former USSR has suffered from disputes over terms of trade, especially over the price of Russian oil exports. In the last year, however, a new problem has emerged: the government’s acute shortage of finance. These financial shortages, which have led to difficulties in meeting budget deficit targets and to major arrears problems in paying public sector wages, are due almost entirely to problems in collecting taxation. By 1996 tax evasion had become rampant. By the end of November of that year, the government was owed an estimated US$9,000 million by large corporations alone, with more outstanding from the republics and regions. Of the total owed by large companies, more than half was owed by oil and gas companies, which in turn are owed large amounts by creditors. The huge state-owned gas production, distribution, and marketing company, Gazprom owed the government US$2,700 million, but was itself owed some US$10,000 million for gas shipments within Russia and the CIS generally. As a result of the revenue shortfalls, the government by the end of December 1996 owed an estimated US$8,000 million in past wages in a wide variety of sectors.

A Agriculture

Most of Russia’s farmland lies in the black-earth belt of the forest-steppe and steppe zones that make up the so-called fertile triangle. The fertile triangle has its base along the country’s western border, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and tapers eastward to the southern Urals, where it narrows to a strip about 400 km (250 mi) wide extending across the south-western fringes of Siberia. East of the Altai Mountains, agriculture is found only in isolated mountain basins along the southern fringes of Siberia and the far eastern region. Areas outside this fertile wedge are unsuitable for crops without human modification. To the north, the growing season is too short without the aid of greenhouses. To the south, the climate is too dry without irrigation. During the Soviet period extensive irrigation works were constructed along the Kuban and other rivers in southern European Russia to support agriculture there; the main irrigated areas of the former USSR, however, are located in the independent Central Asian republics. Agriculture in Russia is generally highly mechanized, and heavily dependent on inputs of fertilizers, insecticides, and equipment such as tractors and harvesters.

In 1999 the agricultural sector accounted for 6.60 per cent of GDP. Production, however, has declined sharply since the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, after rising slightly in the period from 1986 to 1990. In the years 1991 to 1994 output declined by an average of almost 7 per cent a year, with a further decline of 8 per cent in 1995. Thus, overall, in the first half of the 1990s agricultural output fell by more than one third compared with 1990. The decline slowed somewhat in 1996 to about 4 per cent and was expected to level out in 1997. The largest decline was in grain production, which fell by almost 25 per cent between 1990 and 1991, and by another 25 per cent between 1992 and 1994. There was also a significant decline in livestock numbers, which fell by about 30 per cent between 1991 and 1995.

The decline in livestock numbers was partly attributable to lack of animal feed. The decline in crop production resulted from a variety of factors, including lack of reliable credit facilities to purchase inputs like seed and fertilizers; sharp rises in the price of mechanical, chemical, and fuel inputs; and growing shortages of agricultural machinery generally, and spare parts in particular. In 1996, for example, lack of funding meant that barely 50 per cent of land requiring fertilizers was treated. In the same year, as in 1995, much of the harvest was simply not collected because of lack of equipment. Such problems are largely a result of the changes in the Russian economy generally over the past decade, and in the agricultural sector in particular. During the Soviet era agricultural production, like the rest of the economy, was totally state controlled with pricing, interest rates, and profitability centrally administered.